Given the 21st-century backlash against consumerism, it might seem contrary to write a post about my experiences of shopping in Russia, but different country, different era.

What’s more, shopping presented one of the best opportunities we had as students to practise our language skills in a ‘real’ environment outside the classroom.

As I mentioned in my first post about living in Russia in the 90s, after morning lectures had finished, we invariably headed off into the city centre of St Petersburg to see what we could find.

Shops in Russia – even a major city like St Petersburg – were an oddity. Not their existence, rather what they sold.

Buying food

There wasn’t much originality in shop names in 1992. For example, there were numerous places called ‘Moloko’ meaning milk. The irony was that milk was almost never on sale in these shops – in fact, the primary product available appeared to be cognac (the Russian version).

Looking for items of food was always a major element of our excursions into town. Certain items were always available: every second shop’s window display was stacked with jars of pickled goods.

Pickling was of course, a necessary way for citizens to preserve a glut of produce before they went bad (although I didn’t properly understand that at the time).

As someone barely out of my teens, pickles meant one of two things, though: Branston or onions. Pickled cucumber, carrots, garlic, cabbage, tomatoes or mushrooms may have been a Russian delicacy, but ones that I confess I never quite warmed to at the time.

Fresh produce was generally pretty hard to find, especially if you wanted to try and replicate things you were used to cooking as a student in the UK.

There was one large fruit and veg market (that we found) at the time in St Petersburg. There you could find peppers, tomatoes, apples, cabbage and potatoes among others, but prices were pretty steep and, add in the long round trip to get there, regular trips weren’t an option.

Having said that, we did manage to buy two turkeys there for our Christmas dinner. Cooking a full-on festive feast for 25 was no mean feat – we didn’t have enough saucepans so the carrots had to be cooked in a samovar(!). Meanwhile, the cooks in the next-door canteen (who graciously allowed us to use their oven for the birds) refused to believe they’d only take 4 hours. They tried to convince us to leave them in overnight!

Bread was available, but it wasn’t wonderful – until, that is, the ‘shotlandskaya pekarnya’ (Scottish bakery) opened within a 10-minute walk. Again, though, the prices were much steeper than we were used to paying and so it became a luxury rather than a staple.

We also never found out why it was a Scottish bakery either – as far as we could tell, there was no Caledonian connection whatsoever.

Drinking culture

No story about living in Russia would be complete without a reference to drink.

No story about living in Russia would be complete without a reference to drink.

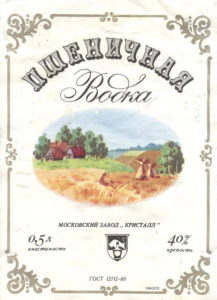

Having noted above how scarce certain food items were, the same could not be said of vodka. But, as was so often the case, it wasn’t the famous (Russian) brands that were widely available.

Stolichnaya and Pshenichnaya (see left) could be found, but were out of most people’s price brackets.

Instead, you went to your local street-corner kiosk. These were dotted all across the city and sold anything from newspapers, cigarettes, theatre and opera tickets (a story for another time) to vodka.

But this wasn’t vodka that came in a nice screw-top bottle. Oh no – the alcohol was sealed in using a foil top, reminiscent of old-school milk bottles. The upshot being, once you popped, you couldn’t stop (the Russians got there way before Pringles!).

It’s no wonder the alcoholism rates were so high in Russia – no-one wanted to waste their precious liquor once they’d opened the bottle.

The queuing culture

Some strange sights quickly became part of everyday life – for example, you’d regularly see people buying sacks of potatoes literally off the back of a lorry.

And while street vendors have a certain cachet in 21st-century Britain, the sight of old women standing on pavements selling individual packets of cigarettes or plastic bags (ironically a luxury in 90s Russia) has always stayed with me. Life was hard for these people.

Queues were a normal part of life – far longer than most have experienced on a day-to-day basis (even during the pandemic). It was a running joke that people joined queues without even knowing what they were for – the theory was that there was probably something worth having at the end.

That ‘end goal’ was also partly down to scarcity. Our motto soon became, ‘if you see it, buy it’. One fellow student saw and bought some clothes pegs early during our stay. Despite rushing off to the shop the following day, they were gone. No-one ever saw clothes pegs for sale again during our time in the city.

In fact, supermarkets (of which there were a few) were faintly-depressing places. The shelves were only ever half full and choice wasn’t a concept that most locals were used to. They were never somewhere we used to frequent that often.

My friend Edward (who I met in St Petersburg) told me about the first time he went to an equivalent UK supermarket on his first trip in 1989, and he almost fainted at the variety available.

In some stores, the system of buying food came with multiple queues. You queued once to talk to the person behind the counter and explain what you wanted. On receipt of a ‘chit’, you queued again to pay (almost always) a woman at the cash desk. You then queued for a third time to pick up what you’d previously ordered and paid for.

We soon spotted there was an art to the queuing. One day, a woman in front of me (buying some cheese, as it happened) turned and said, ‘Excuse me, I’ll be back in a moment’.

She then walked across the shop to join the end of the payment queue. After waiting for a couple of minutes, she turned to the person behind her and repeated the same phrase.

She then left that queue and joined the third ‘pick-up’ queue, repeating her previous behaviour.

This allowed her to pinball between each queue, inching closer to the front, before returning in front of me (very politely thanking me) just before reaching the order counter.

At that point, she was then right near the front of each queue, vastly reducing her stay in the shop – a masterclass at work!

Books and music

Not everything we shopped for was household or kitchen-related, though. Bookshops were a-plenty – Dom Knigi (House of Books) being my favourite.

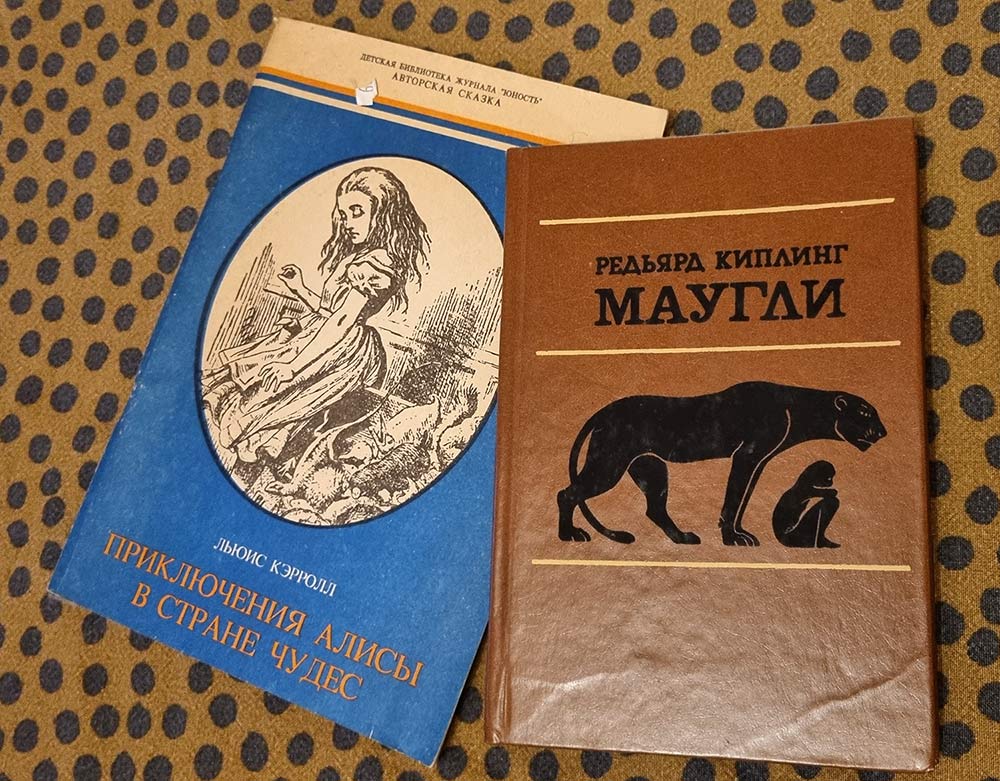

They always reminded me, though, of something out of a Victorian novel – dustjackets were practically non-existent, the shelves were packed to the ceiling, replete with dark-spined volumes, none of which stood out. You really had to hunt to find something you wanted.

Books represented (and always have done for me) a useful way of learning, though. I came back with a variety of Russian-language classics in the original language (Bulgakov, Lermontov, Chekhov, Pushkin and Akhmatova to name a few), but also a few oddities.

As you can see from the above, I bought Russian translations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and The Jungle Book (re-titled Mowgli) – both were a great help to understand the language.

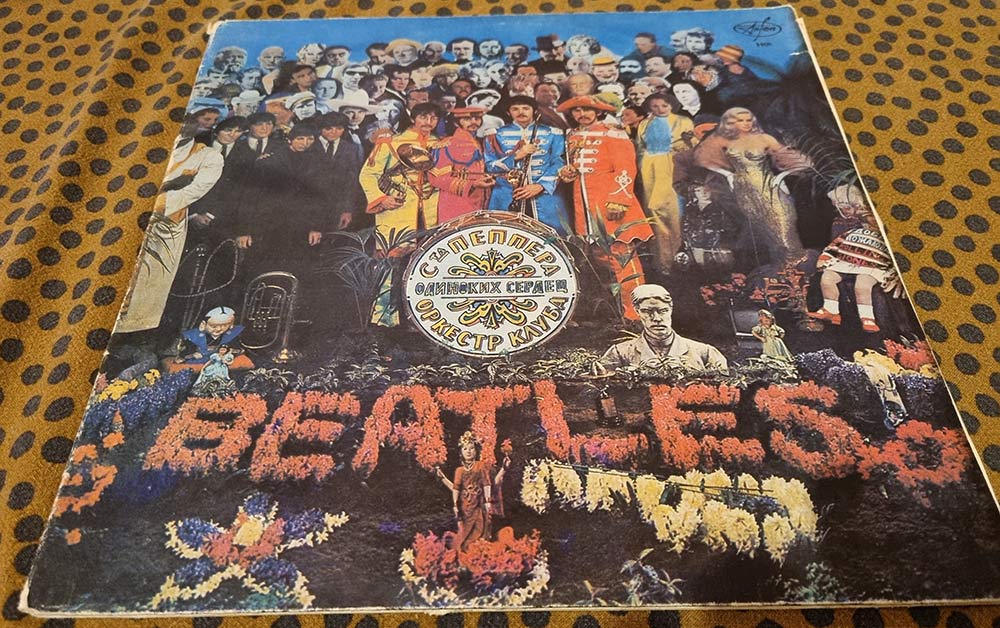

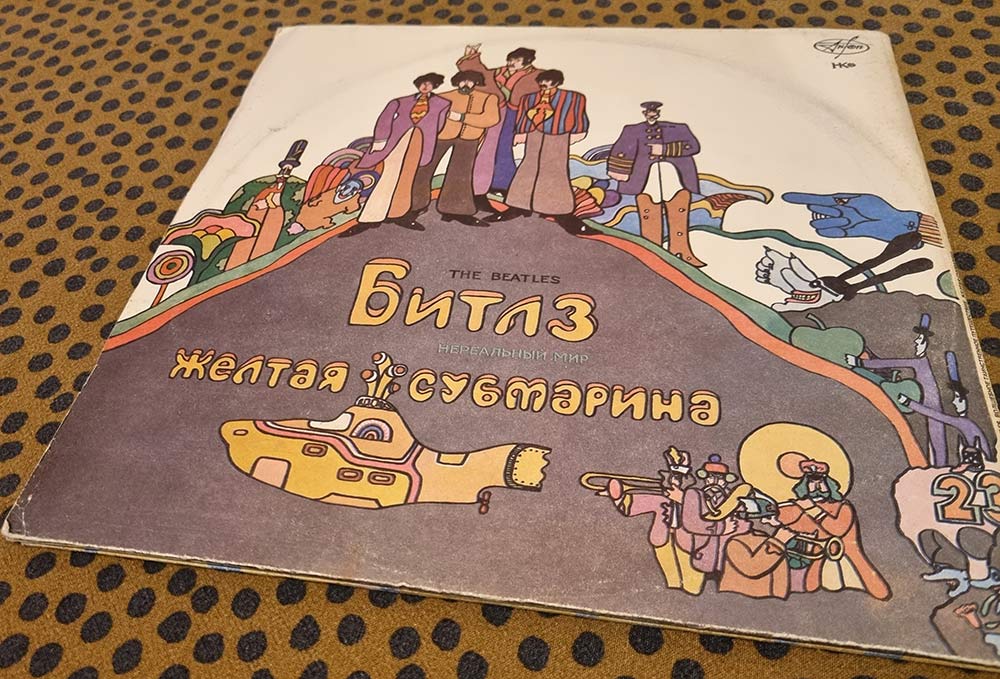

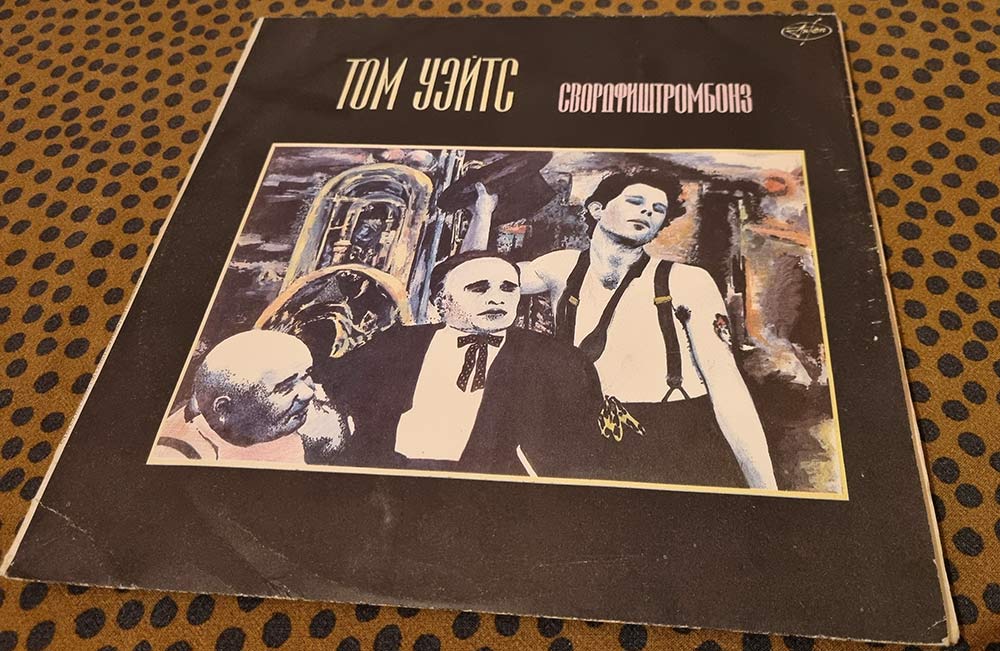

Music was also available, although sporadically and rather randomly. As was the custom, vinyl albums were housed in sleeves that were almost identical, aside from the titles/song titles being translated into Russian.

I bought about 5 Beatles albums, examples of which are below – disappointingly, the recordings were still in English!

My mate Jim, who came to visit, was hugely excited to pick up Led Zeppelin albums in the same format, while it was more than a little odd to see that Tom Waits was also on sale.

—

As you can see, shopping provided a lot of fun and some eyebrow-raising experiences. I’m sad I have relatively little photographic experience of the time, although that’s partly down to not wanting to lug my camera round with me all the time.

In the next instalment, I’m going to focus on entertainment.

Great read! I had heard a bit of this in school, but it’s far better to hear first-hand experience. And an interesting parallel – convenience corner shops in New Zealand are called ‘Dairies’ and I never found anyone who could explain why. At least they did sell milk and other food (though also usually plenty of booze and cigarettes)!

Thanks Susan – I like that fact about ‘Dairies’. It always amuses me when people have no idea of the true origin of an everyday word or name.

The kiosks in St Petersburg were a lifeline – we bought far too much vodka from them!