Last Thursday I went to a fascinating talk at the Wellcome Collection by Dr Alice White.

It covered the work psychiatrists and psychologists from the Tavistock Institute carried out for the British Army during and after WW2.

One part of this covered the selection process for choosing officers and how they helped introduce methods, such as non-verbal reasoning tests, word and picture association and leaderless group activity tasks.

Nowadays these are commonly used, but were fairly revolutionary in the 1940s.

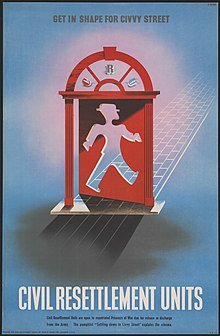

Civil Resettlment Units

As interesting as these were, what I found truly amazing was the Civil Resettlement Units that were set up to help Prisoners of War (POWs) assimilate back into non-military life, following the WW2.

The army recognised (with a bit of cajoling from the scientists) that POWs were a special case and – following the establishment of the Geneva Convention in the 1920s – enemies were obliged to return them to their home country.

But – of course – neither the soldiers nor the public could be led to believe that these men were somehow damaged, hence the rather euphemistic and anodyne name Civil Resettlement Units.

Psychiatrists and doctors rushed to set them up to cope with the influx of returning soldiers and everyone got an invite, whether officer, NCO or regular Tommy.

The CRUs were set up in large country houses and were a place for former POWs to relax, attend workshops and talk about potential careers now they were back in regular civilian life.

There were also dances, whist drives and mixing with the local population, in order to reacquaint the soldiers with normal day-to-day life and – of course – women.

At no point was it indicated these POWs were being assessed by psychiatrists and psychologists. They were there ‘undercover’, as it were, masquerading as medical officers and civil liaison officers.

Did they work?

A study was carried out to assess the effectiveness of the CRUs.

It found that around 1 in 4 (26%) of POWs who went to a CRU became ‘unsettled’ when back in civilian life.

This sounds high, but when you compare it to the almost 2 in 3 (64%) who experienced similar problems, but didn’t go to a CRU, then it appears a success.

The concept and workings of the CRUs were later adapted for European refugees who were displaced by war.

They were also one of the first ever examples of social psychology experiments and yet their existence is still largely unknown. Incredible.